|

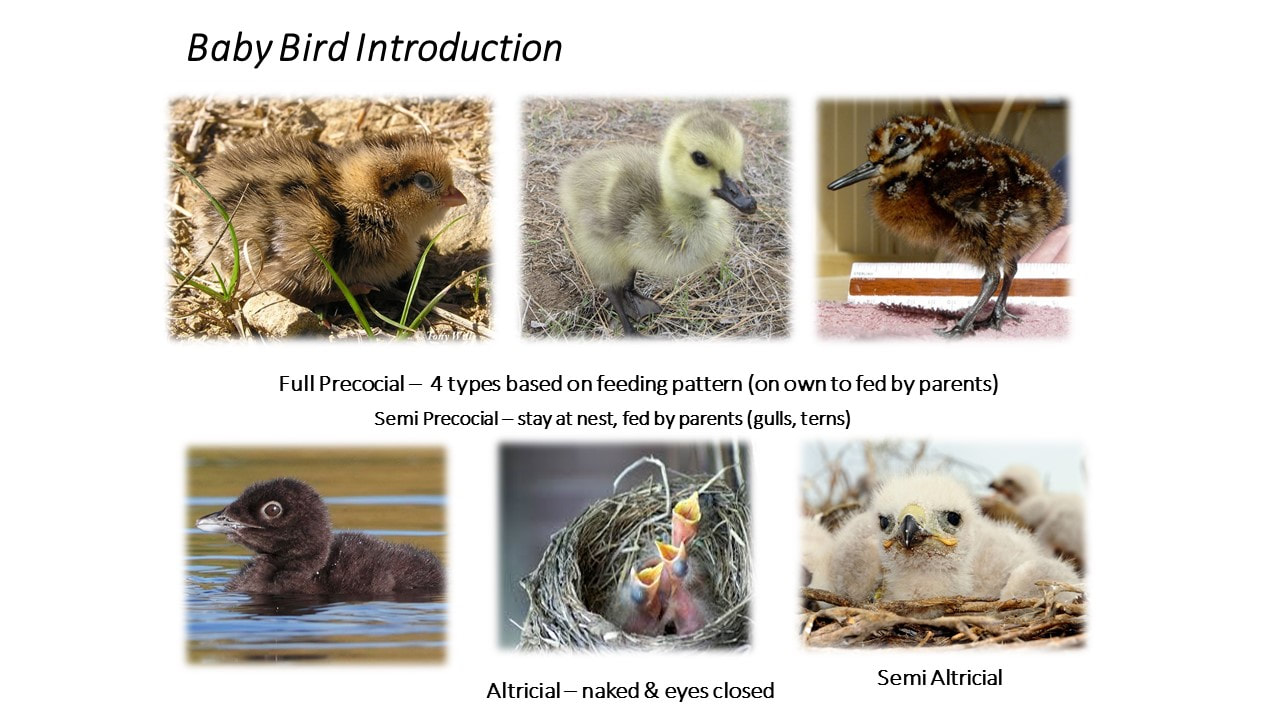

Black-headed Grosbeaks (BHGR) are not only beautiful, but they are fascinating birds. Like so many, they are unique in their lifestyle, how they use their habitats, and, of course, their baby development stages. The images above are of the same bird taken almost two weeks apart. The first image is of the baby upon intake, guessed to be about 10 days old and weighing 29 grams. The second picture is of the same bird, now a fledgling at 25 days old and weighing 47 grams. Neither are self-sufficient or able to feed on their own yet. The younger one can also not keep herself warm or cool (thermoregulate). One is a nestling, the other a fledgling. People often mistake nestlings for fledglings because the internet is full of incorrect information that says feathered baby birds are fledglings. Actually, there are three stages (or four for some species) of baby bird development: hatchling (naked or undeveloped feathers in shafts ('pins'), nestling (feathered with variations of pins remaining to no pins remaining, and fledgling (most birds are flighted at this stage, or they can flutter as they hide deeply in trees and shrubs). The Black-headed Grosbeak does get out of the nest before they can fly. Cornell Birds of the World reports that they leave the nest as young as 12 days. However, those studies involve a lot of nest disturbance by the researchers - and we know that fiddling with, getting close to, or handling baby birds a few days before normal fledging results in babies jumping out of the nest too soon. In the case of this BHGR baby, her (or his) missing feathers around the face, tufts popping out on the head, no tail, and overall development indicate that this one jumped too soon. (Why we took the baby into care). There are many reasons babies jump too soon. The primary reason is predation by any number of omnivorous or carnivorous birds and mammals. For BHGR, Scrub Jays and Steller's Jays are the primary predators. Predators can also include parasites, and nests can be overloaded with bot flies, mites, live, or even ants. Babies might also jump because of nest disturbance (as in researchers handling babies at 12 days old, someone getting close to a nest to photograph, or someone limbing trees and shrubs). Another reason for babies to leave the nest too early is that not all babies may grow at the same rate. In some birds, the parents are not attentive to whether all babies are fed equally. This is true of the BHGR. So, in this species, runts are not uncommon. Our baby indeed had signs of malnutrition (poor head feathering, for example). She's come a long way, though. She is now fully flighted but completely dependent on her mom for feeding. She is toying with foods, sticks, branches, and other things, but her bill is not hard enough to crack a seed, crush a bud, or dig into fruits. She will need to be able to do all of these things as that is the diet of the BHGR, along with insects. With grosbeaks, the bill takes much longer to harden than other songbird babies. Bills are made of both bone and keratin, and in grosbeaks and other birds with heavy bills who eat hard things, it takes time for the bill to develop. Adequate nutrition is paramount for that to happen, so malnourished birds are at a disadvantage. We can only guess what happened to this little one, but she is thriving since she has been in care and provided a nutrition-packed menu. When these babies do leave, they do leave unflighted but with more feathering and further developed than this tyke. They split with their sibling and bury themselves deep in the most dense canopy or shrub they can find. This skill of hiding themselves is why we rarely see BHGB nestlings or fledglings until they are flighted and at a feeder. The female adult would continue to feed her babies for much of the summer. One report found an adult female and her young migrating together, with the parent still feeding the young bird.

So, what do you do if you find a baby BHGR? The best thing to do is not listen to advice that says all baby birds with feathers are fledglings. Second, do not listen to advice that says all baby birds spend time unflighted on the ground. These statements are verifiably incorrect and harm more birds than help them. What do you do?

Hummingbirds are increasingly choosing to overwinter in areas that get blizzards and deep cold. Hummingbirds can suffer and die when deep cold, blizzards, and ice storms set in. Keeping them alive requires warm feeder solution and often another heat source. Hummingbirds in Trouble: NEVER ignore a hummingbird that is clearly in trouble. A bird in trouble will be in a location that seems off, like tucked into a porch, hanging upside down, bill frozen to the feeder, dropping out of the air, falling into the snow, etc. They may also look bedraggled - birds in torpor are neither eating nor preening. Do not leave or ignore birds in trouble!!! Rescue is sometimes necessary. Text us for advice if you are not sure. Read on for how. Can Hummingbirds Survive Intense Weather? Background facts: Anna's Hummingbirds are 4-4.5 grams. On a normal day, hummingbirds must feed every 10-15 minutes; they can starve in hours. They use a physical state called torpor to conserve energy. However, they do not eat or preen in this state. Deep torpor shuts down the metabolism, lowers the body temp significantly, and suspends breathing for periods (up to 5 minutes). Birds that must go into torpor from lack of food, intense weather, or low body fat miss out on eating. This can turn into a deadly cycle in which the bird goes many hours without eating. They must eat everyday to avoid starvation. (Torpid birds are also at high risk for predation). Hummingbirds eat insects and nectar. Their nutrition comes from insects; sugar is pure energy to keep the bird able to forage for insects. Insects give them nutrition; sugar gives them energy. While they can survive on feeder solution alone for up to 10 days in typical temperatures, intense cold requires significantly more energy consumption. Finally, hummingbirds lack the amount of down that other birds have for insulation. Their fat also does not function as much as an insulating layer; fat is more of a gas-station, than a fat layer (like in mammals). This means that they have less ability to withstand super cold and super hot temperatures. (Thus why most migrate). Torpor also means they are not preening, which means the feathers' cleanliness and quality suffer. Poor feather condition results in less weatherproofing and ability to retain heat, leading to hypothermia. The more a bird has to fly around, fighting for a chance at the feeder, the colder the solution, the less healthy the bird, the lower their fat stores, the worse the weather, the poorer their feather condition - the less likely they can survive. Hummingbirds are tough, but there is a physical limit to how much intense weather one can tolerate before succumbing to hypothermia and starvation. Feeder Tips for Helping Hummingbirds Feeders: Icy feeder solution lowers the internal body temperature (thus icy drinks on a hot day). Keep those feeders WARM! The solution and the area ideally. 1) Keeper sugar solution warm. A hummingbird that drinks ice-cold sugar water all day will need to use more energy to warm up. Use a 4:1 solution, not 3:1, which is dehydrating and challenging for the kidneys. Do not use hot water from the faucet due to bacteria; warm it on the stove. 2) Use a home-made or commercial hummingbird feeder heater: a 25-watt bulb for 0-10 degrees; 15-watt for 10-20 degrees; 7.5-watt for 30 degrees. A 25-watt bulb will not keep the liquid warm all day at super cold temps. You will have to switch it out during the day, even with the heater. Holiday light bulbs can burn the birds if they sit on them and are too weak to keep solution thawed. 3) Consider putting up a heat lamp and a perch. Use high-quality bulbs, try to avoid the cheap, thin-glass red lamps. Heat emitters for reptiles are great (if white or black) as they do not have light, just heat. This means the birds sleep better. Hummingbird Heaters 4) What doesn't work: only switching feeders out - sugar water freezes again in a couple of hours; using hot water - again 0 degrees freezes even hot water; holiday lights, like those in picture below, barely do anything to keep a feeder warm. If placed as in picture above, the lights are not even toching the container. 6) What does work: heat lamps (no cheapos, they shatter in deep cold; there are better versions) and feeder heaters are the best options. (0 temp = 25-watt bulb; 20 temp = 15; don't bother with 7.5 watt). Lots of other ideas can work, but check the solution temp throughout the day. (Go to a birding FB page and search 'hummingbird feeder heater'). 7) Placing under the eaves and near the house will keep them warmer. A baffle or cover over the feeder is needed at least. 8) Pet bandaging (Vet wrap) on perches helps retain heat for your hummingbird! Important! Do not use hot water from a hot water tank. They carry bacteria, and hummers can get bacterial infections in their tongues. So, only stove top or electric kettle warmed cold tap (or better, filtered no chlorine or soft water). Evaluating Bird's Condition: There is always a reason for a bird failing. Perhaps s/he simply went too many days in deep torpor without eating. Starvation is a huge risk. Hypothermia could result from the bird being unable to maintain heat because they used up all their fat stores or their feathering is poor condition. Birds with health conditions succumb quicker. Younger birds succumb quicker. Releasing a bird in poor condition will likely result in that bird not making it. Always take a bird to a rescue if there is any question about their condition. Emergency Hummingbird Intervention: Very First: collect the bird or if stuck to the feeder, just bring the whole thing in. DO NOT FEED OR WATER THE BIRD!!! (You can drown them if they are unable to swallow) SECURE BIRD AND WARM; CALL A RESCUE! Stage one: Warmth is always FIRST! 1) Put bird into small box or tupperware on soft, smooth fleece.

Stage 2: Feeding 3) Place the bird in the small box, into a larger box.

4) Release:

Stage 3: Call a songbird specialist rescue center.

Your birds will flock to this easy DIY bird-safe recipe for wreaths, ornaments, or balls. The birds can land directly on these treats without getting any greasy fats on their feet or into their feathers. It is a super easy recipe and being made with gelatin, it is high in protein. This project is fun for kids and not very messy! Please do not use those dangerous home-made suet pine cones that allow birds to get fats all over their feet and into their feathers. Dirty, greasy feathers cannot keep a bird warm, and in winter that is deadly. Ingredients:

For shapes use cookie cutters, the bottom of a Bundt pan, or just mold to the form you desire. Steps: 1. Mix the cold water and gelatin, stir, then wait one minute. 2. Stir in the boiling water until the gelatin dissolves. 3. Add the seed mix to the gelatin water and stir. Make sure all of the seed is coated. 4. Use a cookie cutter, a mold, the bottom of a Bundt pan, or form a shape. 5. Do not spray with oil since this is an oil/fat-free recipe. 6. To form your own shape: use wax paper, plate, or a pastry mat. Shape to whatever joyous or ghoulish image you'd like. Or, press the seed into cookie cutters or the bottom of the Bundt pan till compact, then put in the refrigerator overnight. 7. Create a hole for the ribbon by putting a chopstick or thick skewer into the seed. Hang:

Note: you do not need to add corn syrup or flour, neither of which are good for our birds. Making holiday crafts and decorations safe for our birds is pretty simple if we follow just a few general rules.

Follow our page to learn more about birds, how to care for those who share your yard, and get great ideas like the one here. For the Birds!

As a devoted songbird rehabilitation specialist at Native Bird Care Avian Rescue, I am deeply troubled by the mass mortality event playing out in Chicago. On just one night hundreds of birds hit the McCormick Place Conference Center in Chicago this week. This distressing event has reverberated throughout the conservation community, underscoring the urgent need to confront the issue of bird collisions in North America. With its expansive glass surfaces, prime location along Lake Michigan, and intense nighttime lighting, McCormick Place poses an extreme challenge for migratory birds. Chicago is considered the deadliest city for birds in North America. Thousands of birds will die in this mass death event. Sadly, Chicago is not an isolated case; the trend of the glass-dominated urban landscape is rising in Central Oregon as well as towns and cities across the country. Two overlapping natural events have contributed to this tragedy. A 'high-intensity bird migration' has substantially increased the number of birds passing through the area. These birds are encountering adverse weather conditions funneling them through the city, leaving them confronted with an urban landscape filled with glass walls instead of a natural environment. The Peril of Glass Glass buildings, like McCormick Place, may be architectural marvels, but they are perilous for birds. Bird collisions are a growing concern, with up to a billion birds succumbing to glass collisions each year in North America. Birds collide with glass due to the reflections they see; they see forest when it is a solid structure. McCormick Place's glass façade with large windows that reflect the surrounding environment are an extreme example, but Central Oregon has many bird-collision prone buildings. Birds perceive window reflections as extensions of the landscape and attempt to fly through them, resulting in fatal collisions. Many birds also migrate at night, and bright artificial lights can disorient them, confuse their magnetic compasses, and trap them in illuminated 'walls.' The September 11th Memorial in New York is an example of birds becoming trapped by light. Window collisions lead to severe injuries and often death, making window collisions a significant global threat to bird populations. The Toll on Migratory Birds Chicago is just one of thousands of critical stopover points for migratory birds navigating North America. Each year, over a billion birds journey from breeding areas in Canada and the United States to wintering grounds in Mexico and Central and South America. The species affected by this tragedy include warblers, sparrows, thrushes, and other neotropical migrants. But substantially more species than this are killed by windows. Birds are not just crucial for maintaining ecological balance; their loss disrupts our local ecosystems and poses a threat to the overall environment and human well-being. Solutions The recent bird deaths at Chicago's McCormick Place are a poignant reminder of the challenges migratory birds face today. Yet, solutions do exist. We can implement bird-friendly building designs. We can use after-construction window solutions so our homes and yards are bird-safe. We can reduce light pollution by using appropriate light fixtures and bulbs. And we can raise public awareness about birds and the challenges they face. Many songbird species are in decline; we can contribute to protecting our avian friends during their incredible journeys with simple steps. Let us work together to ensure that our actions preserve the beauty of our urban environment while safeguarding the vital role migratory birds play in our ecosystems and our lives. Please visit our Windows page for simple solutions. If you have questions or simply want ideas on how to keep your precious birds safe, contact us. Please email for ease of us replying. A Great Blue Heron got a second chance last week. The release and his spectacular flight off was covered on KTVZ News, Bend, Oregon. Link to KTVZ spot on release & interview: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1jlI0Wn0m3g Great Blues are our largest heron in North America. They are primarily fish eaters, but will eat just about any animal they can get down their throats - this includes even some birds. In winter, when the lakes and rivers freeze over, they turn to mice and other small animals. You may find one hunting in an open field trying to fill his belly. Young ones, like this bird, can have a difficult time getting enough food when winter really sets in; they must learn to hunt well out of the water and catching mice is definitely a learned skill. This young, first-winter bird was found by a concerned person unable to fly well and huddled against a building. Our volunteer Bud went out and helped capture the bird, a delicate and challenging task given these birds can often still fly a bit. The fact that they have a 5-6 foot wingspan and weight so little means they are can fly until they are very near skin and bones. This results in them only being able to be captured when they are right at death's door, as this young one was.  Great Blue Heron too weak to sit up due to starvation. Great Blue Heron too weak to sit up due to starvation. At half his normal weight (2.75 lbs vs 5.5), the initial days of his treatment and care were challenging. He was emaciated due to him starving for several weeks. As starvation sets in the body turns to its own muscle mass for nutrition. In addition, the organs and intestinal tract can atrophy. This makes getting their bodies going again and digesting and absorbing food a real challenge for us who care for them. It is a slow, delicate process. There is a certain and very specific process we must go through to get a starving bird able to fully eat again. If we fail to follow this process, for example just start giving the bird fish, we can kill them. Patience and knowledge about the birds and this particular form of care is critical.  Great Blue is feeling better, has the strength to sit up on his haunches. Recovery going well. Great Blue is feeling better, has the strength to sit up on his haunches. Recovery going well. This Great Blue Heron juvenile did just fine! He put up with us tube-feeding him for several days, starting out with fluid therapy and certain solutions first, and then moving up to a yummy fish slurry. He was rewarded with fish once he actually started giving us some really nice poops. At the end of care, he was downing about 10 five inch fish a day. All of our patients start out in our large, inside bird rehabilitation room. It was built as large as it is so that we could keep larger waterbirds, like swans or herons, inside in winter. Emaciated or injured birds all need to be kept warm. Their recovery time is far longer if they must produce energy to keep warm. Stress is a factor, but our facility is quiet and remote, so they can just kick back and relax, except for when we come and put a tube down their throats or some other medical care.  Video of Great Blue eating: https://www.facebook.com/elise.wolf.3/videos/372579197960926 Eventually, Great Blue started seriously eating his fish, and leaving us lots of evidence of successful digestion (poops!) in his enclosure (a large 6'x6' padded pen with a large pan of water, which he waded and played with his fish in. LOL). Finally, he got moved out to a large aviary that was set up specifically for a heron, perching logs and large shallow pans of water for wading. Great Blue Heron Factoids:

Birds sustain a number of injuries when hitting windows. Unfortunately, flight is not a sign of wellness. Anyone that slams into a hard wall going 20-30 mph, head first will sustain at least some injury (human or bird). Traumatic brain injury and concussion are the number one injuries. Also, bill fractures, eye injuries, internal injuries, hematomas, coracoid and clavicle fractures, and of course shoulder dislocation and leg and wing breaks. The adrenaline rush from the strike can allow the bird to fly some distance, even with most of these injuries. There, they will succumb to the pain and the injury, and fail to survive due to the inability to forage. Concussion alone causes the inability to thermoregulate (stay warm or cool). Even shock can impair a bird. If a bird hits hard or takes longer than a few minutes to fly off, then the bird needs to be checked and cared for by a rehabber. Always capture the bird as soon as it hits the window if possible. They will be stunned, capture is successful then. Place bird in a small box on a soft smooth towel. If after 15 minutes they are bouncing off the walls, look at the bird. Check eyes and head for blood or feather loss. If none, release. Any bird that sits longer needs at least a phone consult. Any bird that has hit really hard, or has left an imprint on the window must come in. It is expected that most birds that fly off after a window strike ultimately succumb to their injuries or fail to forage well enough to survive. Here's a picture of a fully flighted tanager with a hematoma and concussion. She had to be hand fed for a full week. She would have starved had the finder not brought her in, and caught her when she was in the stunned period. The swelling pushed her eye down into her cheek by day 3 and had to be lanced. She survived. Took a month of care. The severity of her injury took 3 days to develop. First day was just some feather loss. The swelling took days to get to this stage. You would not see this level of injury in a freshly stricken bird. This is why assessment and care saves birds. We are losing 500 million birds a year to windows. Yet window strikes can be 100% preventable. Please check out the windows page for lots of options. Avoid the single decals. Please be cautious about what you put out for birds. There are a lot of home-made suet recipes that are simply dangerous for birds, even deadly.

The fact is fats can get on birds' feathers and harm their ability to stay dry and warm. This lack of weatherproofing and impairment in insulation is deadly in the winter, but also the summer. The most dangerous fats for birds are the soft fats, those that are easily spread. Birds get fats on them by landing directly on a suet ball or feeder and getting the fats onto their feet. The fat is then spread as birds use their feet to preen their heads and for scratching themselves. Fats also spread by a bird having residue on their bill and then preening. The softer the fat, the more fat gets spread. The more hard, dry, and crumbly the fat, the more fat falls off and less get stuck in birds' bills and feet. Greasy birds are dead birds. Oils on feathers impair weatherproofing by interrupting the feathers' structural function. A birds' feathers are like a wet-suit; create a 'hole' in that suit and you get water or cold air access causing the bird to become cold (called 'hypothermia'). Hypothermia kills birds, and often in far less time than one can imagine. Hypothermia can be quick or slow. A bird without sufficient insulation and waterproofing, will spend hours trying to correct the feathers (preening), rather than eating. This results in starvation. A larger bird can live awhile just maintaining as a cold bird who has to eat more, preen more, and spend time shivering more (their way of creating heat). But, ultimately, a stressed life like this would not be long. Getting fats off is impossible for birds. Fats and oils on feathers are difficult to remove and cannot be done by a bird. Avian rehabilitators use a high solvent soap to remove some fats from feathers. True suet, which is what I advise to feed, is actually hard to remove (thus why a caged feeder is imperative). Rehabilitators can get fats off birds, but rarely do we get a chance since dirty birds retreat to a safe tree and perish there. The solution = use safe fats in the suets you feed and always feed suet inside a suet feeder that prevents direct access to the suet or accidental spreading (suggestions below). About Fats Melt points matter! A soft fat that easily melts has a higher tendency to spread. If a bird accidently brushes this fat, it will more easily get onto the bird. If they land on it, it will more easily get on their feet. Hard fat, like suet, is far less likely to get on the bird. Most fats, except true suet and peanut butter, have low melt points - vegetable oils, subcutaneous animal fats, bacon drippings, and many fats misnamed as 'lard' or even 'suet' melt at low temps. Making soft fats hard with ingredients (that birds don't really need like flour and corn) is not a solution; the fat used is still soft. If you can squeeze a suet and leave an imprint with your fingers - you have fat that is too soft. Note that there are cheap suets out there that are like this. All Beef and Pork FAT is not suet! The name 'suet' is getting applied to any kind of animal fat. This is particularly dangerous, and frankly not true. There are various kinds of fats from animals. True suet is the fat around the loin of a cow. It is very dry and hard, thus it crumbles when you handle it. Bacon grease, drippings from beef cooking, fats off steaks or from under the skin, or what is left-over from cooking is not suet - not even close. These fats must have dry ingredients added to them to make them hold together as a 'cake.' True suet, is the safest fat for birds. True Suet: Melt-point of 113 degrees, or higher. A hard, crumbly, dry fat. Yes, it is hard to work with if you make your own suet. However, it is better for the birds. Suet packs a serious energy punch. They do not need to eat very much to gain the fat they desperately need for their reserves and energy needs. This leaves more room for their main dietary foods (seeds or insects). Birds must get as much nutrition out of a food source as they possibly can. Poor food options require more work, less time resting, more stress, and nutritional deficiencies. This is an excellent article on true suet: https://truorganicbeef.com/blogs/beef-wiki/what-is-suet-and-tallow-difference Vegetable oils: Almost all vegetable oils have melting points of 75-77 degrees. This is way too low for a "suet" cake. These fats melt and spread easier, making them a risky option. Low melt points mean that they should not be fed at temps higher than 70. For a 'suet' cake, one must add some form of flour to hold the cake together, usually wheat, corn, sometimes oatmeal. The mix can be as high as 6 cups of flour to a mere 1 cup of fat!!! The bird must eat way more of this concoction to gain the fat benefits than they would a small suet cake (why a true suet cake will last days, and one of these possibly just hours). Please know that corn and wheat, or even oatmeal, have no where near the nutritional composition and quality of the birds' natural or even feeder seeds/foods. For insectivores, filling their bellies with high-glycemic flours instead of nutritionally sound insects results in a nutritional deficit - NOT a gain. This is true for seed-eaters as well. A sunflower seed (one of the most beneficial seeds we feed) is a nutritional powerhouse. A bird taking up precious food space in it belly to eat this low-quality suet is at a disadvantage over the long haul. Are these cakes cheap - yes. And thus the appeal. However, we must ask, are we merely inviting the birds in to entertain us, or are we attempting to offer them a true nutritional advantage? This is an ethical question we all must ask. Peanut butter - Melting point is high, 104, which is the highest. This makes PB one of the safest fats in terms of feather-risk. Suet and PB mixed are an excellent suet cake option (often called "no-melt"); the PB will make the suet easier to mix. Just make sure that the PB has NO ADDED OILS - no other vegetable oils and no sugars. The best kind is fresh ground. (Note: PB can have aflatoxins. Always use pre-made PB or if you use fresh ground, inspect for quality controls. Whole peanuts tend to have more risk of aflatoxin than does PB. Is Your "Suet" Cake Safe?: You can do a quick pinch test to determine how soft your fats (suet fats, lol) really is. Pinch the suet cake between two fingers. Does it squish? Toss it and go for a no melt beef suet that has no or little other oils in it. Note: many commercial more inexpensive suets are like this. They are not using full on suet, but likely a mix of fats. You'll also know if when you handle the suet, your hands are super greasy (hard to get off, right?). If your suet crumbles and is nearly dry - it's real suet. Feeders Cages only please. Never feed suet in a way that allows the bird to land on the fats. They will preen these fats right into their feathers.

How & When to Feed

Recipe Recipe for Favorite suet: Mix peanut butter and suet half and half, you can add some quick oat flour if you really want to, but not much. You can add seeds, nuts, and fruit. I am happy to get tips on this recipe! PM me. PS: Gelatin: Yes, this is safe for birds in limited amounts. Use this to make a seed-heavy woodpecker block. The goal is to have just enough gelatin to hold it together, not be the focus of the food (not that they would eat it anyway). This is a fun crafters project!!! Have fun feeding - do it FOR the birds. Picture is from my friend Jane Tibbetts, songbird photographer extraordinaire! She's made a safe, very neat log feeder for the suet. Thanks Jane!  Do I eat where I poop? Do I eat where I poop? Follow these handy tips for dealing with sick or dead birds at the feeder. Sick birds are still showing up at feeders all across the country. Mainly these are Pine Siskins ill with Salmonella, a bacterial infection. Salmonella can be passed to baby birds from their parents. The species most vulnerable are the smaller finches, like pine siskin and goldfinch, but red crossbills and other birds can also get this disease. Salmonella spread is stopped through disinfecting or removing feeders, and using feeders that are less likely to spread disease. Note that contamination happens as soon as a sick bird lands on a feeder. Basics and Instructions for Cleaning, Feeder Suggestions: *1) If you have a sick bird - remove the feeders for a week or two. Take found sick birds to a rescue. *2) If you have had sick birds, switch to feeders less likely to spread disease - mesh hanging types or hoppers with very narrow feeding trough. Remove feeders that allow a bird to poop into the food! Isolate species by feeding foods specific for the species, see below. *Continue feeding ONLY if you are able/willing to keep the feeders cleaned and disinfected, and able to do this frequently. Fecal matter and saliva are how this disease is spread. Salmonella survives freezing, and hot temps, and lasts a long time in the environment. Bleach is necessary (not vinegar!). Instructions below. *If you are seeing more than one or two sick birds, please change your feeders as they are likely spreading disease. See below. Please explore the instructions below.  If birds can poop onto the food, then they are contaminating the food. If birds can poop onto the food, then they are contaminating the food. What to Do Now: Sick or Dead Birds:

Use feeders that let birds poop on the ground. Cut off seed-catchers, use mesh feeders, hoppers with narrow feeding areas. Use feeders that let birds poop on the ground. Cut off seed-catchers, use mesh feeders, hoppers with narrow feeding areas. Feeder Tips:

Food Choice:

Cleaning Feeders:

Baths & Water Features

Signs of Salmonella: Symptoms: Main sign is a bird sitting listless and not moving. Salmonella causes lesions and inflammation through the digestive track and esophagus. It enters the bloodstream and then organs and brain. Once in the brain it causes mental issues, which is why sick birds act "tame" and they do not fly away. Birds ultimately die from either starvation, since salmonella lesions impair digestion, or organ failure.

What do we do if we find a sick or dead bird?

Living, but sick birds:

Can humans or pets get Salmonella? Yes, but it is not likely. The amounts in bird feces are tiny, and we are large. Cats that eat birds can and do get it. But if you have outside cats, you shouldn't be feeding birds. Chickens carry their own particular subspecies of Salmonella. It too can be spread to wild birds. In fact, agricultural animal waste is one source of Salmonella infection for wild birds, particularly those associated with those animals (starlings and house sparrows). Please use common sense when handling sick or dead birds, and when cleaning your feeders and baths. Gloves are mandatory. If you would like citations for the research mentioned, email us at [email protected] Why Pine Siskins & Finches?

Pine Siskins are particularly susceptible to Salmonella infection. The finch species experienced an "irruption" year in 2020, which is when an unusually large number of a species appears in areas further outside of their range. This trend seems to be continuing, and is likely caused by a shortage of conifer seeds. (Audubon has a nice article on this irruption). You might wonder why the Pine Siskins are ill, while the Chickadees and Nuthatches are seemingly fine. The finch family of birds seems to be more susceptible to both Salmonella and Conjunctivitis. This family includes Pine Siskin, House Finch, Evening Grosbeak, Red Crossbill, and the Goldfinches. Raptors and Owls that prey on sick birds also contract the disease. Notably, this disease was spread from agricultural poultry farms, and more birds who congregate near agricultural animals carry the infection. A few birds will carry the bacteria in their guts, without visible external symptoms. These asymptomatic carriers will shed the bacteria in their feces; if this fecal matter contaminates foods, like at a feeder, then the disease will spread. Some birds are able to overcome the disease and gain enough immunity to survive. This is usually the larger birds, like the Evening Grosbeak. Dr. Wesley Hochachka of Cornell Lab of Ornithology speculates that, "many other species are innately more able to fend off Salmonella infections," and develop immunity. However, given the death rate, he notes that it doesn't appear that this is happening for the Pine Siskin and Redpoll. How & What Diseases are Spread? Birds share disease wherever they congregate and avian scientists confirm that bird feeders are a location in which disease can be passed to other birds (Adelman et al. 2015; Dhondt et al. 2007; Galbraith et al. 2017; Hernandez et al. 2012, Lawson et al. 2018). Many diseases are spread through fecal-oral transmission (meaning the birds accidentally eat poop). Any feeder in which a bird is able to sit in their food is a potential source for infection. Flat feeders and those with large seed catchers are primary culprits. Salmonella is just one of several pathogens that can be spread at the bird buffet. Others are: conjunctivitis, avian pox, aspergillosis, trichomoniasis, and coccidia, along with internal parasites, mites, and feather lice. However, not ALL birds carry these pathogens (just like not all people carry the cold virus). In fact, studies show that only a few birds actually carry the Salmonella bacteria. Salmonella is highly contagious because it survives in the environment (say a bird feeder) for a long time- "several weeks in dry environments and several months in wet environments" (FDA). In contrast, Conjunctivitis survives from "hours to a few days" according to Dr. Hochachka. Humans can reduce disease spread by keeping their feeders clean. Our role in helping these birds is simple. We can create an environment in which the birds have a safe environment to feed.  Well here we are moving into the colder, darker months after coming through such an intense year. We thought we'd share a few happy stories of some of our extraordinary patients that wound up needing help. It was the busiest year Native Bird Care has seen. My first baby songbird came in April 1st, two months earlier than any other season in my 11 years. By mid-May I was already ordering 35,000 insects a week; July is usually when our insect demand is that high. All those babies were for the most part singletons, individuals rather than full nests. In fact, I rarely get a full nest, it is mostly single babies who have wound up alone, injured, and needing help. So, like all baby seasons, I worked a 96 hour work week, it just started way early and did not stop for nearly 5 months. And this year, due to Covid, we could not have volunteers. This fall, it has slowed quite a bit but I still have a steady stream of patients needing care. I hate to play favorites since frankly every one of these birds is an amazing, brilliant gem. I love every one of them, even the most irascible, stressy grouch. In fact, it is pure maternal instinct that powers my ability to get up at 6 am every morning to start putting food into mouths and cleaning up poopy enclosures. The bright spot in avian rescue is the babies, little souls with a desperate eagerness to be a graceful, elegant star, traversing the air or cruising the earth. Here are a few of the stars we had this last year. Enjoy them, fawn over their beauty, relish them as if they are the last one of their species. As we lose bird populations, it is so important to value and cherish every single one of them.  Few birds can match the mesmerizing calls of the Hermit Thrush. The sound from this small 25 gram bird erupts as ethereal waves, flowing from the forest edges. Is that one? Two? The call has a ventriloquist aspect, confusing the human listener, making us wander hopelessly in search of the source of that siren song. To no avail. We've had several Hermits this fall, two were simply too weak to fly, another hit a window, which is quite odd as these are migrants that do not seek bird feeders. Starvation is a real issue birds must face, particularly in this day and age. Finding insects is tough work, requiring a never ending hunt for food most of the day. In care here, we get them past the critical care stage that results from emaciation and then load them up on as many insects as they can gobble down. All our Hermit Thrushes were able to be released amazingly, even the window harmed one.  Cedar Waxwings are one of my favorite babies to raise. This one dropped out of a tree onto someone's patio. We tried for 3 days to find the parents and the nest with no luck. I concluded that this one was a runt, and just was not able to hang on in the nest. She had mites as well and was skinny. She ate like a champ though, enjoying fresh berries and insects. Waxwings, like most baby songbirds, are fed small larvae, caterpillars, and other insects. Mainly soft-bodied bugs that are easy to digest. In care, we avoid mealworms with waxwings and feed mainly crickets and some waxworms. These birds grow up to eat berries however, so we dutifully chop of fresh blue and blackberries, and other fruits. She joined a small flock of other Cedar Waxwings in Camp Polk Meadow.  In July, we had the rare opportunity to help a baby Pied Billed Grebe. All grebe species are 100% waterbirds, meaning that they live full time on the water - eating, swimming, sleeping, and nesting in reeds at lake edges. Sadly, people can easily disturb families like this when they paddle into the vegetated areas at the edges of lakes and rivers. And that's what happened to this little one. Luckily the person found the soaked baby and got her to us for warming, drying, and some food. Over the next week we searched the lake, found a parent, and were able to reunite the one. Her sibling sadly died from the ordeal of being in the water too long. Baby down is not waterproof for long, which is why you see them crawl up on their parents' backs and snuggle in for a ride. Lesson: don't paddle into reeds and marsh.  As happens every year, some crew of Northern Flicker babies find themselves homeless as people remove trees, or exclude them from hole in a house. We renest a lot of these guys over the summer, providing flicker boxes to home owners and moving the babes to the box and out of the home. This works incredibly well, and provides a long-term solution for the home owner looking for a way to keep them outside, not in. Get the ant-eating benefit the Flicker provides, while preventing damage. Win-win! Flickers are a blast to raise. Don't get me wrong, they are a ton of work, but these babies are just so full of attitude and personality. Their tongues and foraging techniques are so very neat. If you go to the videos on the Native Bird Care of Sisters Facebook page, you will see one of our young birds from last year show off her phenomenal tongue eating worms in a tree. We had so many species this year - our fun and common Robins and Goldfinches, Townsend Solitaires, Red Breasted Sapsucker, Black Headed and Evening Grosbeak, House Finches, Red Crossbill, Common Poorwill and Nighthawks, Ash Throated Flycatcher, Hairy Woodpecker, Hummingbirds, Quail, Chickadees, Pine Siskin, Spotted Towhee, and then Spotted Sandpiper, Great Blue Heron, and waterbirds like Lesser Scaup and Canada Geese. And that is not all, here are a few more. I could chat about all of them all day.

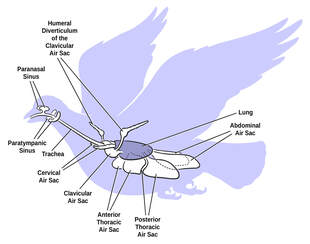

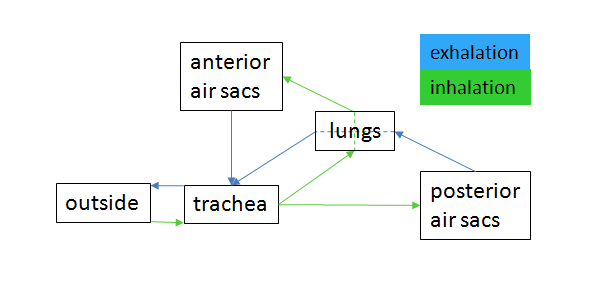

I hope you have enjoyed this look at our birds. Please make a donation this holiday season. Without public support we simply could not keep doing what we do to save birds. Our food bill alone is $5000 a year. Medications, medical treatment and supplies, everything that goes into enclosures and housing, utility bills, and so much more costs a lot. We have no paid staff, so 100% of your money goes directly to the birds that make their way here. Please donate!  Oregon is experiencing the most tragic and severe wildfire event ever recorded in this state. There is significant suffering going on - human, wildlife, and plants. We wish everyone safety and well-being. If you can donate to those organizations that are helping people and domestic pets, and also wildlife, please do. There will be a lot of homeless people and pets at the end of this. We will also have devastating losses of wildlife and their habitats. Yes, it will recover. It may take a long time though for some species to regain numbers. These fires are not friendly cleaners, they are too intense for that. I've been asked how birds handle fire. I am no expert, but here's what I do know. Generally some birds will fly away, escaping the coming inferno. In massive fires like this one, some may not make wise choices in the directions they choose and suffer. Some may not realize the epic nature of the fires coming and choose to hunker down, staying in place to ride it out (like some people try to do). As birds move around they are often forced into new habitats where food resources may not be ideal or they are unfamiliar with. Fires may encourage migration as well for those species heading south. Birds traveling through in migration will hopefully simply fly on past, however, with much of the Cascades on fire, we can only hope they have the reserves and physical capacity to keep going. They will face more challenges as they hit the fires raging throughout California. I look forward to seeing some research on the movement patterns of birds experiencing fire. I do know that a lot of animals are dying right now. That is a given. I am not getting many as most birds will perish without anyone seeing them, as we are all stuck in our homes. I hope that anyone who finds a suffering bird will text us and give the bird a chance. We do not have the fire staff on these mega infernos for anyone to rescue animals while out on the front-lines. I am sure they wish they could. How Does Smoke Affect Birds? Birds lungs are incredibly complex and extraordinary. In fact, the incredible physical accomplishments of birds - flight, long distance trips, and endurance - are in large part due birds' breathing anatomy. Birds do not have just two lungs like us mere land-walkers. They have up to 9 "air sacs" - balloon-like structures that allow lightness and enormous breathing capacity. Each breath of a bird passes through all of these sacs and the lungs before being exhaled. The entrance to birds' airways is located at the bottom of the mouth, not the back of the throat like mammals. It is called the "glottis." This odd location allows more efficient and immediate air intake, which aids in the aerial feats birds engage in. (The location of the glottis and the risk of aspiration is a main reason feeding baby birds is actually a developed skill. It's super easy to get food or water into their airways, and birds cannot cough to force anything out because of how distributed the air becomes once in the body. In some birds, like the Common Poorwill, the glottis is darn near the front of the mouth, with the tongue very tiny and seemingly vestigial. This anatomy translates into a rather complex breathing operation. Note in the picture below, the air comes into the body, passes through the trachea, goes into the posterior air sacs and the lungs. The air in the posterior air sacs goes on into the lungs and back out. The air that goes into the lungs passes through the anterior air sacs before exiting the body. What this anatomy results in for birds' airways is that what goes in, stays in. So the micro to larger particulates of smoke, wind up going into birds' air sacs and lungs and not leaving. Just like us, these particulates can cause inflammation and impair intake of oxygen. The health effects of smoke are the same as for humans, except they are magnified by the fact that birds are more efficient breathers and retain more particulates.

In sum, smoke inhalation can and does kill birds. It impairs their ability to breathe and that impairs their ability to forage and sustain themselves. Birds will often sit is stasis. They may go to the ground as the air can be clearer there. Birds will often head into the canopy where they are a bit protected from larger particles and predators. Smoke also dirties birds' feathering, which can lead to birds ingesting this pollution as they preen. Keeping clean is imperative for birds ability to stay weatherproof, so they will try to seek out water. The chemicals and pollutants in the smoke is not good for them, so the cleaner they can stay by bathing, the better. So what can we do to help? Keeping clean, fed, and having access to water is critical for all the birds suffering right now. So, if you want to help your yard birds, please consider turning on sprinklers for an hour or so a day. Please wear a mask as you go outside to protect your lungs. Keep all feeders full, and clean the water baths and features as much as possible. You can also add additional trays of water, placed around the yard. Most birds we will not be able to help as they are simply not yard birds. However, if we are backed to open space or forests, we can help these birds by aiming sprinklers out where a few might get some benefit. Migrants who are desperate for food or water can benefit too from us putting water out. Putting food on the ground like millet will help the ground feeders and those that will eat millet like the finches. Keeping feeders full is important. And keeping bird baths clean! With so many birds taking baths and with the particle buildup, we want to keep the baths clean. Why do some act like nothing is happening? Still going about their day. Well they simply have no choice. Little birds in particular must eat much of the day, every day just to survive. As smoke impacts them, they can succumb from lack of oxygen and lack of food if they cannot eat. Birds waiting it out may go without food, leading to starvation. We can do almost nothing for the birds that do not come to the feeder. Note, putting water pans out helps other animals too, if you happen to be able to put out large pans for the deer and others, I advocate that. Smoke dehydrates everyone...no you should not feed the deer, their food is still there. But adding more water to your landscape cannot hurt. Yes, we are in a drought and water conservation is important. So please, do always conserve water as a general rule. If you see distressed birds hunkering down, rescue them. Put them in a box and text us. Please keep kitties inside right now, for their health and for the birds that are coming to the ground where the air is cleanest. For yourselves, tape shut any vents, hang blankets over doors, avoid going in and out, get an air cleaner going, and try to close up leaks. We wish everyone the best...please pray or say blessings for rain....  Fledgling flicker probing log for insects. Note pink tongue, which can reach 3". Fledgling flicker probing log for insects. Note pink tongue, which can reach 3". People often ask us for advice on what to do about Northern Flickers. Birds' relationships with us and our homes result from their attempt to navigate a human-altered environment they have no control over. Solutions should be sought with a compassionate and friendly attitude. The Northern Flicker is a critically essential habitat species. They are one of our largest woodpecker species and can deliver hard and deep enough blows to create a cavity in nearly any tree. These colorful, energetic habitat creators provide needed cavities for many other tree-nesting species - owls, kestrels, ducks, small mammals, and songbirds, including chickadees, nuthatches, and swallows. They are a 'keystone' species, meaning other species who would otherwise be unable to create their own cavities rely on them. Cornell Lab of Ornithology says, "The loss or diminution of the Northern Flicker would likely have a large impact on most woodland ecosystems in North America."  Carpenter ant colony Carpenter ant colony For the home-owner, a positive attribute of the flicker is that they are predominately ant eaters - often consuming entire breeding colonies of carpenter ants. They are mainly ground-foraging birds but will also eat insects found on or inside trees, like wood-boring beetles. If you have insects on your home, like from old siding or old stain/paint, these birds will help clean up the house. So, keeping the siding in good shape is important. In Central Oregon, these stout birds love the Juniper because this sought-after habitat tree will remain standing though its insides have begun to rot.. Many cavity-nesting species - many of whom we see at our feeders - use Juniper for its incredible ability to have multiple cavities throughout the tree. So, if you like flickers, keep your Juniper and snags.  Male on right, female left, courtship Male on right, female left, courtship Flicker drumming is what most people struggle with come spring and is a sign of the male letting the world know about his nesting territory. The drumming is also a way to get a new mate or get his current mate in the mood, so to speak. While the drumming might indicate the bird wants to make a nesting hole in the home, it is more often simply a non-vocal call that does little to harm the house. The louder, the better, so metal roofs and gutters are of prime interest to flicker males. If the drumming is intolerable, the birds are causing damage by trying to excavate a nest; we must find a solution. Finally, due to habitat loss (natural and human-caused), cavity nesters compete vigorously for nest holes. Starlings are another key reason flickers lose out on cavities. Solutions! Male excavating nest hole Male excavating nest hole Tip #1: Let them drum! One of the easiest solutions is to ignore them. If they are drumming on metal, like on gutters, it will likely not cause damage. At Native Bird Care, we have successfully 'trained' our flicker male to drum on the back gutters by ignoring and allowing that while shooing him off other parts of the house. If you relinquish the gutter, then they may leave other areas of the house alone. Flickers stop drumming once they have successfully established their territory, which does not take long (about two weeks at our center). They are only territorial regarding their nest sites, not food - so this is a short-lived period. Tip #2: Stop feeding suet and hulled sunflower seeds. When we invite wildlife to our yards by feeding them, we also invite all of their other natural behaviors. Chasing them off our homes while continuing to feed them pushes them into neighbors' yards and onto others' homes. There is simply not enough natural habitat in the urban landscape for their nesting. Keeping dead or dying trees (snags) and Juniper in our yards provides homes for these birds. However, we should all think more about the 'carrying capacity' of our yards and local area landscapes, which is how much food (insects) and territory there actually is for all the nesting species we may be inviting with boxes and bird feeders. Tip #3: Dull the sound and prevent access. There are two solutions for eliminating or reducing the sometimes mind-numbing drumming. A) Deaden the sound using products. If the drumming site is metal, duct tape or rubberized coatings work well. Do NOT use sticky tapes or other harmful solutions; these are illegal and cause unnecessary suffering for the bird by coating their feathers and harming their weatherproofing. C) You can also put up cardboard or wrap cloth around the gutter. You will need to treat all areas of the home that are most sought-after - they will be at or near the top of the house, usually metal. B) You can also enclose the area, say a chimney, with chicken wire or box it in to discourage drumming.

c) Hang netting, sheets, or sheers off the eaves or entirely down one side of a house using cup hooks or out away from the house using plant hangers. Netting works best if it is hung taut; otherwise, it can become a risk to the bird. Tarp, canvas, or netting can be used up in the eaves and installed at an angle to prevent nesting holes. Netting is an affordable and easy solution for this purpose and for keeping birds from striking windows. d) Be sure to block any eave holes (BEFORE nesting season). Wood or sheet metal can cover holes and prevent further damage. Caution! Please never use these exclusion ideas AFTER the birds have already created a nest hole. Exclusion materials can cause the birds to abandon their nests and eggs or babies, which is illegal due to the harm they cause to the birds.  Tip #5: Flicker boxes. Boxes are increasingly suggested as a near-total solution to flicker issues. However, bird boxes should only be put up when the situation is right for the birds. See below. Simple Rules to Follow: a) Flicker boxes should be no less than 23" tall and 18" from entrance hole to floor. The floor should be no less than 6" x 7". When purchasing or making a flicker box, look carefully at the dimensions! There are a lot of poorly designed nest boxes on the market. And, because a box was handmade, it does not mean it is a good box. This rule also applies to box plans (the NestWatch plans have a floor that is too small for Flickers). Flicker babies are large; too small of a floor space cram them together and can lead to undeveloped, starving babies and poor feathering.  b) Always put grooves up all four sides of the inside box walls. Flicker babies start to perch vertically on the cavity walls at about two weeks. There will not be enough room on the floor for the babies, even with a 6x7" floor. Being gregarious, flicker babies need space, so make sure they have use of the entire inside of the box. If you make the box, this is easy, use a small saw to make 1/4" depth grooves about 1/2" apart horizontally up the walls, going all the way across. On the front, ensure the grooves go all the way across so babies can push each other aside to get to the hole for food. Vertically perching babies will be more equally fed and have far better plumage. A tail in good condition is paramount for woodpeckers. c) Pack wood shavings (pet bedding) into the box enough to make it firm. Aspen bark is best as it is not dusty (bad for bird lungs), has fewer splinters, and lacks the sap other tree species have, which can get on baby skin and growing feathers. Flickers need to excavate to become physically able to produce young. They will not use empty boxes, and packing the box full excludes starlings.  d) Location: Proper siting and location is paramount. Base site decision on the home's himan activity in June and July - not April. Place ideally in a southeast corner for morning sun.Flickers will tolerate activity and humans untill nestling stage (this is true of most our of urban nesting birds). However, once the nestlings are able to flap a bit, they can easily get spooked from their nests/cavities and leave too early (which leads to death by predation or exposure). Flickers are far more likely to use a box on the house; they look for the lagest 'tree' and that is your house. Chose the most private, least stressful place - not above a door, or social gathering areas. Younger birds may not have the experience to know they are making a housing faux pau until it’s too late (one way I get baby birds). Placing the box on the house also works best if you have a small yard and the house is the best 'tree.' If you want to exclude a current flicker’s hole-building project on your own house, try putting up a box over that hole. Another location option is on a metal conduit pole out in the yard at 8’-12’ high. This prevents predators being able to climb up and get into the box. Place 10’ from nearest tree, in the shade, facing South or Southeast. Like humans, birds can make awful real estate choices. If this has happened, a licensed professional with proper federal permits might be able to relocate the birds. Landscapers, pest companies, your neighbor, and you should never attempt a nest relocation. Improper relocation is most likely going to kill the young birds. Birds recognize their young by EXACT location, not just their calls. Contact us for advice. A nest box on the house is excellent for smaller cavity nesters tapping on the home - nuthatches and chickadees. You can often simply place a box right over the hole they are making. Giving them a box can prevent the birds from not being able to find a nest cavity when the female is close to laying her eggs. Simply fill the created hole with a sealant and place the nest box over it. Put two inches of the aspen bark in the box. Ensure the box also has grooves all the way across the front wall, not just under the entrance hole, so babies can get alongside and push dominant, bigger babies away from the hole. Grooves should be 1/8" inch deep by every 1/8". Placement and location are same as Flickers. Never put perches on bird boxes unless you want to feed predators. What is 'carrying capacity' and an 'ecological trap'?  Two week old flicker babies. Note the white stripe on head. This is where the tongue attaches. The little red baby has malnutrition and was not able to get enough food. (Yes, she survived just fine with care!) Two week old flicker babies. Note the white stripe on head. This is where the tongue attaches. The little red baby has malnutrition and was not able to get enough food. (Yes, she survived just fine with care!) Should I use a Nest Box?

Flickers feed insects to their babies and young, and their babies need incredibly high protein content to be nutritionally sound enough to grow stout, fully functioning bodies that will allow them to survive. Feeder foods ARE NOT APPROPRIATE for babies! Do not be misled by marketing language that calls certain feeder foods good for nesting birds or babies. It is not! Babies need wild insects (mealworms are not enough and there are issues with them). The average nesting territory for flickers is about 330' in circumference. They are large enough birds to fly some distance to find food for their young. Their nesting territory will vary based on how rich the habitat happens to be and the competition for their food sources (lots of ants). If there are flicker boxes on many homes in an urban neighborhood and the habitat is only marginally productive in insects, then those babies are at risk. When choosing to use bird boxes, please consider the amount of territory the birds will need, the quality of the habitat, and what competition the birds might face. Did you know some precocial birds are fed by their parents? Loons, shorebirds, coots for example. Only 2 truly precocial birds exist, and they are not in North America. Anyhoo...will continue this later...

This is a nestling Western Wood Pewee. She came in after her nest was blown down after a heavy wind. She was a hoot to finish raising. As an aerial insectivore and eating by catching her insect prey in flight with her feet, she took some extra care getting her ready for release. Babies like this need practice catching their food, so giving her flighted insects was necessary. We do that with bot fly larva and fruit flies (which we make ourselves by...you guessed it...lots of old fruit scraps. Basically we leave a bucket of rotting food out in the aviary with 1/4 inch screen on it so birds cannot get in, but bugs can get out. I would also toss crickets and mealworms in the air for her to catch...she was super adept early on and kept getting better. She learned way faster than her barn swallow buddy who would just look at me from his high perch and shun my attempts. He eventually got it though and both would swoop down to catch what I tossed up. Notably, she caught her bugs with her feet and the swallow caught his with his mouth - both variations on on-the-wing foraging by birds. This little Pewee was surely one of the sweetest birds we have had in care. She got released with a whole flock of other Pewees at Camp Polk Meadows. Birders helped us locate a flock, then we took her to them. She flew directly towards the flock and two came out to greet her. Absolutely perfect!

American Coots are abundant, that's true, but it doesn't take away from them being a fascinating, beautiful, and unique bird. These cuties navigate inland waters year-round, and they fit in a similar niche as a small grebe (like a Horned or Eared). But they are actually part of the Rail family (along with Virginia Rail). Rather than skirt the shoreline like a Virginia though, these guys are eating small fish, crustaceans, bugs, invertebrates and vegetation along the shore while in the water. They are floaters, not walkers. Like the grebes, these birds cannot take off from the ground due to their feet and the size of their wings (which are small in relation to their body size and weight, which is an advantage if you are a swimmer). So, these birds wind up stranded in poor winter weather (like loons, grebes, and ruddy ducks). This girl rebounded remarkably once we dewormed her, warmed her up, and got her fed and hydrated. In fact, she put on 200 grams in 9 days (its amazing how quickly they can respond once the problem is found!). Like other waterbirds that come through here, we made sure her feathers and waterproofing were in shape, and maintained, and she got a pool. Had we not already put our winter pools away (oops, who knew winter would be in March!), she would have had a bigger pool, but instead she had to do with our large indoor water set up, which is a whole lot more work for us as it has to be cleaned very frequently so she stayed clean. (Note - next year, leave winter pools up in aviary!) Why the red eyes? Lots of waterbirds have red eyes as it helps them see underwater. Note the babies have brown eyes, red eyes happen as they reach adulthood. Their leg color also changes, from more green/olive to more and more yellow as they age. And while Grebes and Loons have toenails, nothing compares to the talons on these guys. Just check out the first picture. In fact, these feisty birds will flip over on their backs like a raptor and try to slash you with those sharp, hooked nails (yes, we ALWAYS wear gloves with Coots, ha ha!). The boys are another 200 grams on the girls, so they can be a handful (2 handfulls, ha). The lobes on those pretty yellow-green feet are designed to propel them through the water, highly effective paddles, very cool.

We had the fun time of raising a baby coot last summer. So for fun I've added a parent and two babies. Notably, like most waterbirds, Coots also feed their babies bill to bill. So, even though they are born "precocial" (born with down, able to move away from nest soon), they cannot feed themselves. This is such a wonderful picture of their colorful, adorable babies. Coots may be one of the few birds that can make the global transition we are experiencing, because they are adaptable, can eat a diversity of food, and are productive. Go Coots!  A big thanks to Spencer in Ontario who rescued a Horned Grebe! Finding my website which highlights these birds, he called for help, which I was happy to offer. The horrible cold and storm in the mid-west is likely bringing quite a few of these birds up onto the shore or onto parking lots and roads. They come out of the water if they are either frozen out or have lost their waterproofing (like from contamination or bad body condition). I hope more downed ones are found. Always rescue a grebe out of water, and never simply put them back in. They are out for a reason and need help. Horned Grebes are some of the cutest birds there are. Looking like mini-penguins, their feet are positioned toward their rears to enable efficient swimming. They have a hard time standing for this reason. Like a lot of waterbirds, they have smallish wings that are held tight to their bodies for streamlined swimming (though they do not swim with the wings). The foot position and small wings makes it impossible for them to fly from stand-still. They must run on water for up to 20 or more feet to get into the air. Thus, once down, that's it if they hit pavement. These cuties breed in AK and Canada mainly, with just a few in the states. They winter in coastal regions, from Alaska to Mexico and Nova Scotia to Florida, also winter inland on lakes and rivers at various locations throughout the US. Horned's eat lots of larvae and insects, as well as small fish. They have charming breeding behaviors and the male and female have similar plumages in breeding season and winter. They mate up during winter, and are monogamous; some continue their relationships for several seasons. These birds wind up coming down in bad storms and when lakes or rivers freeze over. They will hop onto land if frozen out and basically sit there, helpless and at risk of starvation or predation. They also come down if migrating and hitting severe weather. They wind up emaciated, hypothermic, and at risk of death. Huge numbers of these birds have come down in harsh storms in parking lots and roads. But when the single birds get downed, it is a bird that simply does not have the stamina from poor body condition. These birds are prone to parasites (worms), which cause them to be in poor condition and weight. Worm infections can ruin waterproofing as well. can be Birds that I get ALWAYS have worms and are always hypothermic. We follow care protocols similar to those of the seabird-specialist facilities , so every bird gets wormed asap here. However, these birds, if they are in migration, reduce (atrophy) the size of their internal organs. This makes them unable to receive the normal level of food intake. This is a key reason these birds must come into rescue. First, we must access their physical status, including whether they are in a migratory condition.

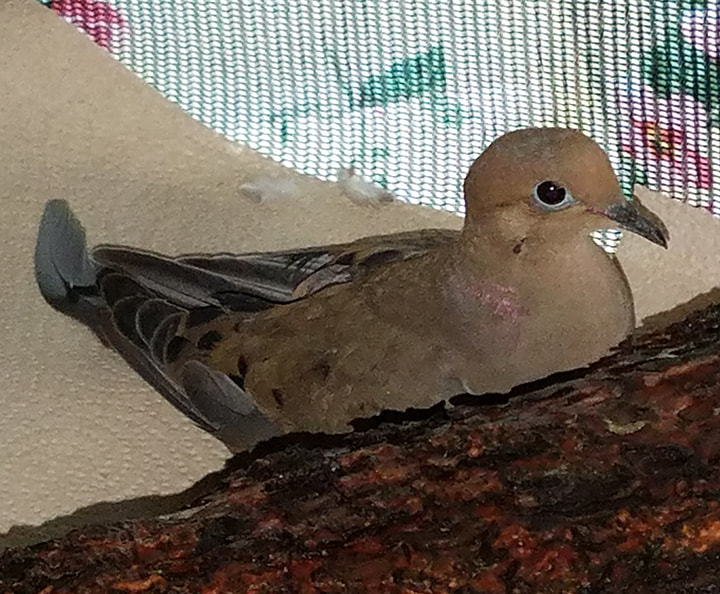

Downed birds are always cold. Sitting on cold pavement or snow (and given they came down due to condition), would make anyone cold. Putting them back into cold water will either kill them or they will get out again. Hypothermia kills wet, cold birds. Getting them warm is critical. Like all seriously hypthermic patients, including humans, they cannot simply be set on a hot pad. They must be warmed slowly and hydrated. These birds special water facilities to regain their waterproofing and hydration. So, please make sure to call someone if you find one. Never simply put them back on water, call a wildlife rescue and get a consult with a rehabilitation professional who knows these birds. I am happy to answer questions and help find a facility wherever you are. A huge thank you to Spencer for caring for this wonderful and unique bird. And thanks for driving him 3 hours to save him!!! Finding rescues who take these birds and can help them sometimes requires some looking. Spencer - You rock! Mourning doves are just so precious and gentle, and so pretty. The subtle coloring on them is really beautiful. The one in the back, a boy, came in late fall injured from a cat attack. All of his skin and feathers were torn off from the mid back down. It took a month of wound management to repair the damage. That sort of repair is always stressful just due to the potential infection. But, he pulled through just fine. His new skin is healthy and ready to grow feathers, so we are just waiting for him to finish that process. And he has to grow a tail. The gal next to him came in after hitting a window really hard. She had a fairly serious hematoma around her eye. Luckily all was fine once the swelling came down. I put her with the other guy so they could keep each other company. She runs over to him when the scary woman comes in. No, they do not get that I won't hurt them. Doves are very stressy birds. They will be released together, and perhaps we will have helped them find love together. I really adore these birds, but they are one type that are just frustrating in care. Their key defense is to blow out their feathers - and I mean a LOT. You will notice that neither has their tails. Earlier today the girl did, but she decided to let them all go when I went in to clean the cage. I have a protocol that works with this behavior, its called 'let them be.' They will both grow their tails back once in the aviary.

A little science: The right picture is an excellent example of what a "blood" feather looks like (the dark shaft at the bottom of the picture). This is what a feather looks like when it is just growing in. A feather grows out in a protective sheath that holds blood to grow the feather. The blood has all the nutrition for growth of the feather. A bird that breaks a feather low at this stage will bleed. Feathers are fragile at this point. Eventually, the full feather grows in and the blood section shrinks down to nothing. These two are doing great, and they will be released as soon as they both have all their feathers and tails back.

It takes soap for us rescuers to get fats and oils out of a birds feathers - they simply cannot do this themselves, neither their bills nor their saliva is able to do this. Birds groom their heads with their feet, so even if their belly feathers do not wind up soiled, they can easily spread these fats to their feathers by grooming with feet that have fat on them. Myself and several other songbird rehabilitators are quite concerned about this growing trend and get fat contaminated birds in which we must bath to save. Don't trust me? Smear your hands with any oil or fat you are feeding your bird, now go try to wash it off using only water. I use Dawn soap to get suet and fats out.  Belly feathers and feet touching fat= deadly for birds. Greasy birds are dead birds, as lack of waterproofing, allows water to contact their skin, which then makes them cold, cold birds spend more time preeing then eating, once very cold thats all they will do and slowly starve to death. Cold wet birds starve or die from hypothermia. Key to fats are their melting points and fats like suet with high melting points are safest. Note the following melting points are for ambient air temp, not direct sun - note any time fats are exposed to sun that temp can get high even in cold weather. Direct sun starts to melt any of these on contact which means always feed fats in the shade. Here are some facts. Takeaway 3 is that the only safe fat is suet. (and some kinds of peanut butter if fed correctly. Suet: a particular kind of beef fat found around organs and groin. Raw it is hard, crumbly, with far less water and no blood veins as is found in general beef fat. Its melting point is about 110 degrees. It is used raw in recipes (mainly British). Beef fat; must be rendered (melted down and sterilized) to be made hard enough to form and to kill bacteria. Melting point is 95 degrees. This should not be used for feeding birds. First, though its melting point is 95, surface melt is more likely to occur, making any home suet greasy. Rendered beef fat is not "suet" - you can get it hard, but still its low melt point makes it risky for birds' feathering and waterproofing. (Regions with zero degree weather, 24 hours a day, this can work, like Fairbanks). Vegetable oils: Coconut and palm are the only plant fats that are hard at room temperature. Their melting points are 75-77 degrees. This is way too low for a "suet" type of bird food. Also, birds likely do not have the digestive enzymes to digest these oils. In contrast, you will see even songbirds pick at dead animals, which is likely why eating our suets was not so hard to get them to do. Animal proteins and fats are closer to the types of foods they eat, at least the insectivores. Peanut butter - melting point is high, 104. Just make sure that it has NO ADDED OILS - no other vegetable oils and no sugars. The best kind is fresh ground kind - where you pour the peanuts into a machine and you get fresh peanut butter, no salts, no oils, no sugar. Added to suet, this makes a "no melt" sort of suet. Recipe for Favorite suet: No Melt peanut butter & suet. Ground oatmeal, corn flour or finely ground, quick oats with its flour, rendered suet. Add peanut butter if you want a no melt. You can add seeds, nuts, and fruit. Please ALWAYS USE A SUET FEEDER...either a cage or something that encloses the fats. You can use logs if they are hung so that the bird cannot get the fat on them (vertical is usually required for this AND if they have a landing perch. NEVER EVER EVER SPREAD FATS OR OILS ON TREE LIMBS!!!! I cannot express how dangerous this is for birds. And you will NOT notice their demise, unless you are banding and keeping watch for months. What I am saying here is common sense, not that hard to reflect on why this is bad. Audubon and others sites have fine print that comment about the impact of fats on feathers. Native Bird Care and other Songbird rehabilitators are currently pressuring Audubon and other organizations to stop promoting this fat fad and the impacts its having. Note that even on a cage, a bird can get its feathers exposed to fats. The cleaner your cage feeder, the safer for the bird. The colder it is, the likely the suet will crumble off the feet, rather than melting.

They look larger than they really are, at only 2 or so ounces. They are tiny really. They live almost entirely on fruit in winter, and today they have moved towards more of our planted species, like the mountain ash. However, they get their name from the Cedar tree, which they ate the berries of historically. They are highly susceptible to the insecticides and other sprays with coat our trees and shrubs with. And being so little, it does not take much to make them sick. At least 2 of my intakes were sick from what I think was pesticide poisoning. One did not survive, the other I just released. If you love birds, please do not spray your trees with anything...not even "non-toxic" products like soap (soaps kills the waterproofing on birds and makes them sick too). These are not feeder birds, but if you want them in your yard plant serviceberry, mountain ash, cherry trees, crabapple, and raspberries - but be happy birds are eating all your fruit! Know that your fruiting trees are keeping these cuties alive. In rehab, they are eating soaked currents, pear, chopped raisens, raspberries, and blueberries, along with mealworms (at least they are offered). Unlike some birds in which we try to return them to their original location and group, with the Waxwings, we release them to larger flocks with abundant resources (if we can). Cedar Waxwings are flocking up at this time anyway and we like to give our rehabs a good chance. There is safety in numbers, and they have night-time buddies to stay warm with on freezing nights and experienced birds that can lead the way to food sources.

Enjoy these special birds! Keep some small binocs in your car, and take that moment or two just to get close up look. However, never walk up to trees at night and try to get closer looks at birds resting for the night or even on really cold days. Once a bird flies, it loses all of its built up heat. Birds can die from having to lose this critical heat upon a flight made late in the day. For the tiny songbirds, they may not have the physical reserves to make more heat for their frigged night. Enjoy those Waxwings! See the fb post for video. Mountain Bluebirds must be one of the most beautiful songbirds that grace our skies here in Central Oregon. I was blessed this summer to be able to save 4 baby mountains who had sadly lost their parents somehow. The kind home owner who noticed this, intervened after a day and called us. The babies were a bit burdened by parasites and a bit thin, and of course quite hungry, but luckily nothing else was wrong. So, in they came. We are careful to interview people when they want to bring in a full nest of fairly healthy birds. But in this case, their body status did indicate that the parents were struggling to feed them and they needed treatment for mites. With even one parent missing, if the family is having difficulty feeding already, then having a missing parent would have meant a slow starvation for these sweeties. Its nice when owners observe and watch the nest boxes they have. Not only is it fun for them, but they know right away when birds are having a hard time. This summer was difficult for many insectivores since June was really frigid and then we shot up into the 90s, both temperatures take their toll on bugs...and thus baby birds. These babies lucked out and got all the bugs they needed from us! This summer we created a large indoor aviary because the hot temperatures in July were making the aviaries quite steamy. We often mix and match baby birds once they are fledging so that they have the sense of being with a larger flock (but only if they get along!). Other older birds too can help the younger ones learn to eat out of dishes on their own. The bluebirds had as company a Townsend's Solitaire, Barn Swallows, and 2 feisty Lesser Goldfinch. It was very sweet to see them perched all together at the end of the day. About Mountain Bluebirds These beautiful birds are in the family as the American Robin - they are thrushes. And of all the thrushes they eat the most insects. This is why we do not see them at our feeders and instead out in wide open meadows and sometimes agricultural lands. They love caterpillars, but eat many flying insects as well. They also glean insects from trees like aphids which makes them good for the forest. You will see them perched on fences and on tree limbs on the edges of a forest meadow waiting to flit out from their perch, grab the bug, and land again. They can also hover and dive bomb. Ground insects are not safe either, these expert insectivores will spend some time on the ground hunting beetles and crickets. In Central Oregon we get to enjoy these sweet birds year-round, some winter here from northern climates, while others are local migrants moving from different areas for breeding or wintering habitat.